The Green Sheet Online Edition

May 12, 2008 • 08:05:01

Another 100 years of cash?

My paternal grandmother used to open a novel at the back page in order to read the ending of the story first. So I will give you the ending of this article upfront and then work my way back, unveiling in the process the secret of cash's enduring popularity.

Here is the conclusion: There is virtually zero chance that cash will be withdrawn from society within the next generation. That is, in the next 25 years. And in all likelihood, there could easily be another 100 years of cash.

This conclusion is only remarkable because there is a widespread perception in financial services that cash's days are numbered. People talk vaguely about the cashless society. Some folk seem to believe that plastic and digital forms of money are set to replace cash.

Upon analysis of the true nature of cash and on what is driving global demand for cash, however, this conventional wisdom turns out to be based on a myth.

It is a fantasy which has been promoted largely by the card-issuing sector because it has a vested interest in the demise of cash.

But the cashless society is about as real a possibility as the paperless office. At this stage, it belongs in the realm of science fiction.

As head of the ATM Industry Association, which represents a broad spectrum of the ATM marketplace in about 50 countries, last year I sought out a futures analysis of cash. After all, cash remains the lifeblood of the approximately 1.7 million ATMs worldwide, since about 70 percent of all ATM transactions are cash withdrawals.

But I half expected to read evidence that the cash industry had about 10 to 20 years of life left in it.

I soon found that the story of cash, like all good stories, has a twist to it, an amazing element of surprise. During my months of research, I was astounded to discover that all the indicators showed that cash appears to have a bright and unlimited future.

The conditions keeping it in production are much stronger than all the growth inhibitors and threats to its existence.

A cash tour

It is true that overall global market share for cash as a form of payment declined in the latter part of the 20th century - because of the advent of the credit card, POS terminals, Internet banking, and new options such as prepaid cards and mobile banking. Yet the value and volume of cash continues to climb throughout the developed and developing worlds.

One source told me the estimated annual demand for new banknotes is 1 billion. The Bank of England, European Central Bank and U.S. Federal Reserve System all report that U.K. sterling, the euro and U.S. dollar currency in circulation continue to increase.

The U.K.'s payments association, APACS, reports that 91 percent of payments in Britain worth less than 10 pounds are made in cash, that's compared to 5 percent made by debit and 2 percent by credit. In fact, Visa Inc. estimates that $1.3 trillion per year is spent on small ticket items.

De La Rue Currency, which annually conducts a payments survey, says cash remains the preferred means of payment for 58 percent of the U.K., particularly where small-value payments are concerned.

And cash accounts for two-thirds of all personal payments by volume in the U.K. In 2006 alone, 36.3 billion pounds in cash was spent in supermarkets.

Even for payments exceeding 50 pounds, Britons are more likely to use cash than credit. And nearly 2 million Britons are still paid in cash on a weekly basis, according to APACS.

By the end of 2004, the value of notes in circulation in the U.K. exceeded 36 billion pounds, a 45 percent increase from 1999.

One of the most pervasive myths about cash is that its usage is declining in advanced economies. But that false view assumes cash is for less-advanced, developing countries. Let us take Europe as an example. This continent has done more than any other region of the world to encourage the decline of cash.

The European Commission and European Payments Council are promoting noncash payments through the creation of a cashless payment system called the Single Euro Payment Area.

And in France, authorities have limited use of cash by law, for example, saying that transactions exceeding 3,000 euros may not be conducted in cash and wages may not be paid in cash.

Yet Europeans continue to draw more and more cash every year.

The European Union has set a benchmark of between 200 and 230 noncash transactions per inhabitant per year, while Spain, Italy and Poland see fewer than 100 noncash transactions annually.

Across 17 European countries, the average person makes a modest 49 card transactions per year. And the EPC estimates there were about 360 billion cash transactions in 2003, compared to 60 billion noncash transactions that same year.

Euros in circulation also are growing at a rapid pace. Europe's volume of cash has grown about 20 percent per year since the euro's introduction in 2002; by 2006, 1.3 billion euros were in the market. In the euro zone, volumes of low-denomination notes have been increasing at 5 percent per annum - a rate higher than inflation.

Advanced countries like the United States, Japan and the U.K. maintain resilient cash usage. The Bank for International Settlements reported in September 1999 said notes and coins as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) rose from 1990 to 1997 in Japan, Germany, Canada, the United States, the U.K., Italy and Australia.

And according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, paper currency continues to climb in America, from $380 for every American in 1975 to $2,578 in banknotes per American by 2005. In addition, an extra $35 billion in coins is rolling around, clearly supporting a deluge of circulating cash in the world's greatest economy. The value of U.S. dollars in circulation increased 400 percent between 1980 and 2005, from $160 billion to $700 billion.

Japan, the world's second-largest economy, is cash-dominated. Only 36 noncash transactions are made per person per year, compared to 288 per capita in the United States - and 119 of those are conducted in the form of checks.

In so-called transitional countries, such as the former Soviet Union, cash dominates in volume and value.

And in Australia, cash remains the payment method of choice for small retail transactions and money transfers between individuals.

In fact, the ratio of currency to gross domestic product is increasing in Australia, up to 4 percent in 2004 from 3.5 percent in previous decades. Cash payments make up 40 percent of value for all retail payments in Australia; in food and convenience stores, cash accounts for about 56 percent of all sales.

In South Africa, the Reserve Bank reports annual increases of 10 percent in the demand for cash. Two-thirds of all transactions are still conducted in cash, with 55 billion rand worth of banknotes in circulation and up to 3 billion rand in cash exchanging hands every day. About 91 percent of South Africans use cash to pay for groceries, while 4 percent use debit, 3 percent use credit and 1 percent use stored-value cards.

The increased global demand for cash is good news for the ATM industry, because the cash machine remains cash's primary distribution channel. In the U.K., 87 cash withdrawals at ATMs are made every second. In 2006, U.K. consumers withdrew 180 billion pounds in cash from ATMs, with average withdrawal value being 65 pounds.

According to World Payments Report 2006, the aggregate number and value of ATM cash withdrawals grew at an annual rate of 5.9 percent and 7.1 percent, respectively, from 2000 to 2004.

Scan Coin, a global leader in cash processing, reports that cash handling is increasing by between 2 percent and 10 percent in most industrialized nations, and the percentages are much higher in less advanced countries.

And cash-recycling technology is expected to improve future cash efficiencies. England's Retail Banking Research says cash recycling at self-service terminals in Europe is expected to grow 30 percent in 2008. According to current estimates, that rate of growth will increase by 170 percent by 2010 and 215 percent by 2017.

Manufacturing the myth

So what's driving the cashless society myth?

Futures thinking tends to overestimate technological change and to underestimate the role of people, culture and society. The simple truth is that most visionaries of the cashless society don't understand the history of cash.

The use of coin stretches back to Lydia in the 7th century B.C. And paper currency's origin can be traced to China's Tang Dynasty circa 618 A.D. How many other technologies can claim to have survived that kind of span?

It's the simplicity of cash that has resulted in its longevity. Cash produces instant results virtually anywhere on earth. That is an immense strength. Cash is not a technology that easily reaches exhaustion because of resource depletion. And cash has a strong resistance to substitution.

In 1979, Michael E. Porter of Harvard Business School developed a theory of five forces that shape the competitive environment for businesses and products. One force that threatened businesses was product substitution, which would make it more likely for customers to switch to product alternatives, especially when prices increase.

Porter outlined components of product substitution, including a buyer's propensity to substitute, the price of substitutes, switching costs and the perceived level of product differentiation. Given that cash has proved to be an interepochal technology, how has it fared against the threat of substitution?

The check, the first product designed to substitute for cash, was extensively used for the first time in Holland in the early 1500s. But in five centuries, the paper check has failed to replace cash.

And then there is the credit card, which came out of a New York restaurant in the 1950s. The credit card has been a remarkable piece of technology, but it may be comparatively short-lived, because of its inherent risk.

And the economic downswing isn't expected to help credit's cause. In fact, in China, the world's future superpower, credit is not regarded as real money - real money in Chinese culture is cash in the bank.

The credit card, too, then, like the check, has failed to topple cash.

Whether we talk about mobile payments, Internet payments or gift cards, each one is likely to absorb some market share of some payment technology. The payments landscape is multichannel, and somewhat cannibalistic. But no one payment device, whether an electronic funds transfer, a mobile phone or a prepaid card, can substitute for cash.

Cash is valuable, fee-free for consumers, tangible, carries certainty of acceptance as legal tender, settlement-immediate, free of credit risk, a public asset regulated by the central bank, anonymous and cannot be tracked, easy to access and use, universal, and interchangeable with other cash. Cash also is fast.

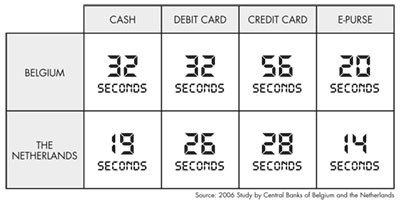

The following chart compares the number of seconds it takes to complete cash, debit card, credit card and e-purse transactions in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Such speed is important in retailing. McDonald's Corp. reported that shaving six seconds off transaction times brings about a 1 percent increase in sales. Global remittances also are driving the use of cash.

The World Bank estimates that the total amount of remittances sent home in 2005 to developing countries by workers abroad reached $173 billion. That estimate is now thought to be closer to $310 billion.

The good thing about remittances is they help bridge the divide between the wealthy and poor. Levels of poverty have declined in countries that receive remittances on a large scale.

Recipients use the money they're sent to improve their children's education and to provide living accommodations. Remittances are often received in cash, sometimes via ATMs.

Tourism also is driving the use of cash. In 2003, tourism represented 6 percent of the world's export of goods and services. And tourists prefer to use local currency when they travel abroad. An estimated 70 percent of Chinese tourists prefer cash on their travels.

And if remittance and tourism aren't convincing enough, the future existence of cash is virtually guaranteed by the growing role of the informal sector - defined as economic trade not registered for taxation.

The informal sector, which excludes organized crime, is growing in developed, developing and transitional countries. In the EU, 48 million workers are part of the informal sector. In India, informal-sector trade provides more than 90 percent of employment with some 360 million workers. In South Africa, 25 percent of the labor force works in the informal economy, responsible for 10 percent of all retail sales.

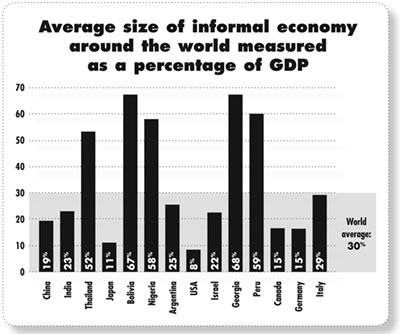

And in Russia, the informal sector makes up 14 percent of the country's total employment. The accompanying table accompanying shows the significant role of informal trade in the global economy.

The global average size of informal trade is about 30 percent of GDP. Which government is seriously going to try to eradicate that level of trade from within its boundaries and thus risk pushing up its unemployment rate and poverty levels?

Notice to readers: These are archived articles. Contact information, links and other details may be out of date. We regret any inconvenience.